Why do corals release mucus?

Corals are known to release mucus from their body into the water. But why do they release mucus? Look at the above picture. When I expose corals to air, they release slimy mucus. In a natural environment, corals can be exposed to air during extremely low tides, experiencing high temperature and dryness under strong sunlight for a couple of hours.

In a natural environment, corals can be exposed to air during extremely low tides.

You will see a copious amount of mucus released from the corals, which is a defense mechanism against desiccation. Corals coat their body with mucus, keeping in moisture to withstand severe environmental conditions.

Corals also release mucus under submersed conditions for several reasons. Here, I summarized the reasons (see table below). Generally corals release mucus under stressed conditions such as defense against biofouling, pathogens, UV radiation, sedimentation, pollutants, and desiccation. Even water currents and temperature or salinity changes can be a cause of mucus release.

Corals use mucus to remove sediments

Summary of mucus release factors by various corals

Source: Nakajima & Tanaka (2014)

Corals also release mucus under non-stressed conditions. They use mucus as a tool to capture prey items such as bacteria and small zooplankton with their sticky surface. Corals transport the food items trapped by mucus into their mouth using ciliary movements (Lewis & Price 1976). Corals are also known to release mucus as excretory pathways for excess organic matter (Tanaka et al. 2009).

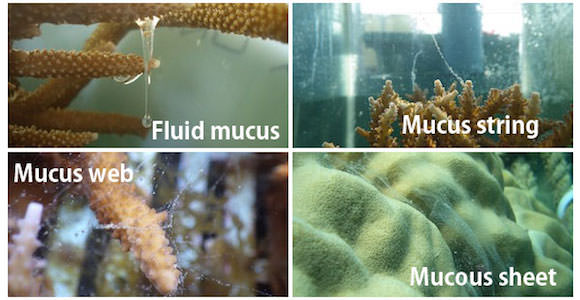

Appearances of coral mucus

The origin of mucus comes from zooxanthellae, a symbiotic algae (Meikle et al. 1987). Studies show that corals release approximately half of the photosynthetic products (organic matter) provided by zooxanthellae into the water in the form of mucus, while they use the rest of the organic matter for growth and respiration (Crossland et al. 1980, Davies 1984, Muscatine 1984). The coral mucus is primarily consisted of sugar-protein, called mucin, and polysaccharides and lipids. Coral mucus used to be defined by various terms such as fluid mucus, string, web or flocs, and mucous sheet.

Various forms of coral mucus

Nowadays, however, mucus is commonly separated by the difference in size from a quantitative perspective, that is POM (particulate organic matter) and DOM (dissolved organic matter). DOM is technically defined as organic matter that can pass through filters with a pore size of 0.7-1.0 micrometer.

The size of organic matter strongly affects subsequent pathways. For example, DOM in reef waters is mainly taken up by heterotrophic bacteria and incorporated into the microbial food web. On the other hand, the larger POM is utilized by reef fishes, zooplankton, benthic animals; it also partially sinks down and is mineralized in the sediments. Therefore, information about the sizes of the organic matter produced by corals is important for understanding the subsequent biological availability and carbon pathways.

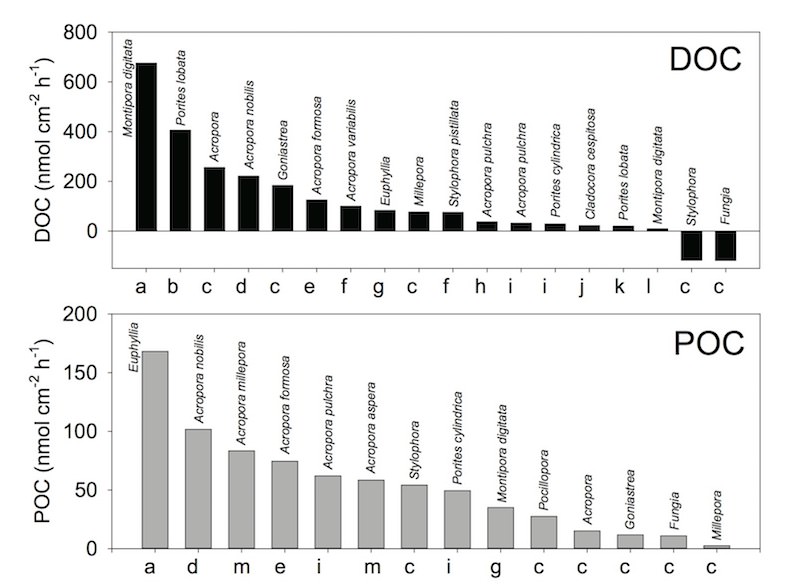

Mucus production rates by corals

Now let’s look at DOM and POM production by corals. Look at the next figure. This figure is the summary of release rate of DOC and POC by various corals (as of 2014). The x-axes indicate reference sources. As you can see, both DOC and POC release rates vary greatly, ranging from -120 to 680 nmol/cm^2/h for DOC, and from 3 to 170 nmol/cm^2/h for POC. It’s not even easy to estimate the averaged values!

Summary of release rate of DOC (dissolved organic carbon) and POC (particulate organic carbon) by corals. Modified from Nakajima & Tanaka (2014) a Wild et al. 2012, b Levas et al. 2013, c Naumann et al. 2010, d Nakajima et al. 2009, e Nakajima et al. 2010, f Crossland 1987, g Wild et al. 2012, h Tanaka et al. 2009, i Tanaka et al. 2008, j Herndl & Velimirov 1986, k Haas et al. 2011, l Tanaka et al. 2010, m Wild et al. 2005

These large ranges of DOC and POC production rates could be caused by various factors, such as species differences, the surrounding environmental, and experimental conditions. Here, I would like to discuss further about the differences in the experimental conditions.

When you measure the production rates of organic matter released by corals, usually the corals are incubated in a closed system like beakers or bottles for a certain period of time (such as several hours). Now, look at this table (below). Many conditions differ among these types of cultural experiments, including incubated medium volumes, incubation times, type and intensity of provided lights, seawater temperature, and the stirring conditions of the medium.

Different methods for measuring mucus release rates

Modified from Nakajima & Tanaka (2014)

| Incubation method (medium vol., L) | Incubation time (h) | Lighting | Stirring | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottle (1) | 3-4 | Fluorescent lamp | No stirring | Herndl & Velimirov 1986 |

| Flow through chamber | 3 | In situ | Flow through | Crossland 1987 |

| Beaker (0.5-2) | 4-6 | Shading sunlight | No stirring | Wild et al. 2005 |

| Bottle (8) | 96 | Direct sunlight | Continuous | Haas et al. 2011 |

| Plastic bag (2-8) | 24 | In situ | No stirring | Nakajima et al. 2009 |

| Bottle (0.7) | 5 | Halogen lamp | Continuous | Nakajima et al. 2009 |

| Beaker (0.8-1) | 6 | Shading sunlight | No stirring | Naumann et al. 2010 |

| Bottle (1.8) | 5 | Direct sunlight | Every hour | Nakajima et al. 2010 |

For example, higher light intensity could increase the photosynthetic rates of zooxanthellae in corals, which increases the release rates of DOC and POC from the coral colony (Naumann et al. 2010). Higher nutrient concentrations in seawater might reduce DOM release rates because the production of zooxanthellae cells is promoted with nutrients and less organic matter is available for release (Tanaka et al. 2010). These differences in experimental conditions among studies might cause the large ranges of POC and DOC release rates (Nakajima & Tanaka 2014).

You can see a pattern of DOM and POM release by corals, however, when you look at the studies measuring both DOM and POM release simultaneously. Generally, corals release more DOC than POC into the water. Approximately, 60-90% of organic carbon is released as dissolved form (Naumann et al. 2010). So the majority of organic matter released by corals would be mainly utilized by bacteria.

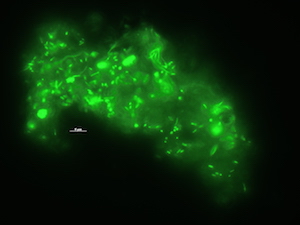

Microbial decomposition of coral-derived DOM

Microbes on coral mucus, stained with SYBR Gold

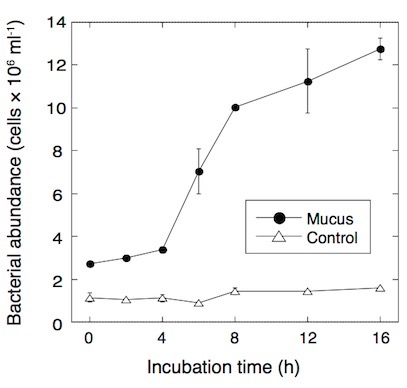

Fig. 3. Development of bacterial abundance in seawater after addition of coral mucus. Modified from Nakajima et al. (2015)

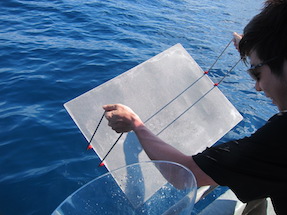

The rapid bacterial growth can subsequently lead to the emergence of bacterivorous protists such as heterotrophic nanoflagellates, which are capable of transferring carbon to the higher trophic levels through the microbial food web. To test if coral mucus enhances the growth of bacterivorous protists in situ condition, I examined bacteria and protists in the sea-surface microlayer over coral reefs. The sea-surface microlayer is the thin boundary layer between the atmosphere and ocean, with a typical thickness of 10-250 µm. The sea-surface microlayer is generally enriched in both DOM and POM and microbes.

Coral mucus often includes air bubbles that provide buoyancy, which slowly ascend to the sea-surface and accumulate. Passing through the water column, its sticky surface traps various organic particles such as bacteria. So coral mucus contributes to the formation of enriched organic matter and microbes in the air-sea interface. Also, higher coral coverage in an area can mean higher organic matter or coral mucus input, which results in a more stimulated microbial community at the air-sea interface compared to areas with lower coral coverage.

Sea-surface microlayer can be collected using this kind of mesh screen (mesh width: 1mm)

I have also experimentally confirmed that the growth efficiencies of both bacteria and bacterivorous protists were higher with coral-derived DOM, suggesting higher transfer efficiency from bacteria that is fueled by coral organic matter to bacterivorous protists (Nakajima et al. 2017).

How great is the nutritional values of coral mucus?

Coral mucus is utilized by various reef animals including fish, zooplankton and various benthic animals. Here, I summarized the list of animals that have been reported to feed on coral mucus, which are either isotopically or visually confirmed.

Summary of organisms that feed on coral mucus

Modified from Nakajima & Tanaka (2014)

| Taxonomic group | Species | Method for feeding experiments/observations | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish | |||

| Blue sprat | Spratelloides delicatulus | behavior | Johannes 1967 |

| Damselfish | Chromis sp. | behavior | Johannes 1967 |

| Damselfish | Chromis sp. | behavior (no feeding on mucus was observed) | Coles & Strathmann 1973 |

| Surgeonfish | Acanthuridae | behavior (no feeding on mucus was observed) | Coles & Strathmann 1973 |

| Butterfly fish | Chaetodon ornatissimus | behavior | Hobson 1974, Reese 1977 |

| Plankton | |||

| Copepod | Acartia negligence | 14C incorporation | Richman 1975 |

| Copepod | Acartia tonsa | neutral red dyeing/[methyl-3H]-thymidine incorporation | Gottfried & Roman 1983 |

| Mysid | Mysidium integrum | neutral red dyeing/[methyl-3H]-thymidine incorporation | Gottfried & Roman 1983 |

| Crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) larvae | Acanthaster cf. solaris | 13C, 15N incorporation | Nakajima et al. 2016 |

| Benthos | |||

| Coral crab | Trapezia sp. | behavior | Knudsen et al. 1967 |

| Coral crab | Tetralia fulva | behavior/carmine dyeing | Patton 1994 |

| Coral gall crab | Hapalocarcinus marsupialis | behavior | Kropp et al. 1986 |

| Coral gall crab | Utinomia dimorpha | behavior | Kropp et al. 1986 |

| Shrimp | Coralliocaris superba | behavior/carmine dyeing | Patton 1994 |

| Shrimp | Philarius imperialis | behavior/carmine dyeing | Patton 1994 |

| Shrimp | Jocaste japonica | behavior/carmine dyeing | Patton 1994 |

| Crab | Mithrax sp. | behavior/neutral red dyeing | Stachowicz & Hay 1999 |

| Bivalve | Lithophaga lessepsiana | 14C incorporation | Shafir & Loya 1983 |

| Softcoral | Pseudoplexaura porosa | 14C incorporation | Coffroth 1984 |

| Acoelomorph worm | Waminoa sp. | 15N incorporation | xx |

Then the question arises as to how great is the nutritional value of coral mucus. In order to figure out the nutritional values of coral mucus, we can use the protein/energy ratio. The protein/energy ratio is often used to estimate nutritional values of food items (Wilson 2002, Wilson et al. 2003). Energy (or calories) can be calculated using the following assumptions (Henken et al. 1986):

- carbohydrate = 4.2 kcal/g

- protein = 5.65 kcal/g

- lipid = 9.45 kcal/g.

Here, I calculated the protein/energy (P/E) ratios of coral mucus using the basic composition of carbohydrates, proteins and lipids of coral mucus from various corals (see Nakajima & Tanaka 2014 for details).

Summary of energy/protein (P/E) ratio of coral mucus

Protein/energy (P/E) ratio (mg/KJ)

| Coral | P/E ratio | Mucus form | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungia | NA | fluid | Daumas & Thomassin 1977 |

| Acropora formosa | 16.3 | fluid? | Meikle et al. 1988 |

| Pachyseris speciosa | 24.1 | fluid? | Meikle et al. 1988 |

| Fungia fungites | 35.7 | fluid? | Meikle et al. 1988 |

| Acropora | NA | fluid | Ducklow & Mitchell 1979 |

| Platygyra | 35.2 | fluid | Ducklow & Mitchell 1979 |

| Fungia | 2.7 | fluid | Ducklow & Mitchell 1979 |

| Faviidae | 8.3 | fluid | Daumas et al. 1981 |

| Lobophyllia corymbosa | 20.6 | fluid | Daumas et al. 1981 |

| Platygyra | 11.9 | fluid | Pascal & Vacelet 1981 |

| Fungia scutaria | 17.1 | fluid | Krupp 1982 |

| Porites furcata | 11.4 | fluid | Coffroth 1990 |

| Porites astreoides | 17.6 | fluid | Coffroth 1990 |

| Portites lobata | NA | fluid | Coffroth 1990 |

| Porites sp. | NA | fluid | Coffroth 1990 |

| Porites sp. | NA | sheet | Coffroth 1990 |

| Porites australiensis | NA | sheet | Coffroth 1990 |

| Porites divaricata | 30.7 | sheet | Coffroth 1990 |

| P. lobata | 26.5 | sheet | Coffroth 1990 |

| Porites lutea | 25.1 | sheet | Coffroth 1990 |

| P. astreoides | 27.9 | sheet | Coffroth 1990 |

| Porites murrayensis | 31.6 | sheet | Coffroth 1990 |

| P. furcata | 28.7 | sheet | Coffroth 1990 |

Mucous sheet

What if I compare these nutritional values of coral mucus with other food items in coral reef environments? Well, here is the summary.The nutritional values of coral mucus are comparable or even higher than those of reef benthic algae, reef algal detritus, reef fish feces, phytoplankton and zooplankton. That’s why coral mucus is one of the best nutritional sources!

Fig. 4. Summary of protein/energy ratio of some potential sources for zooplankton. Summary of Fig. a Wilson et al. 2003, b Wilson 2002, c Bailey & Robertson 1982, d Renaud et al. 1999, e Ventura 2006

Acknowledments

Drawing by Adi Khen